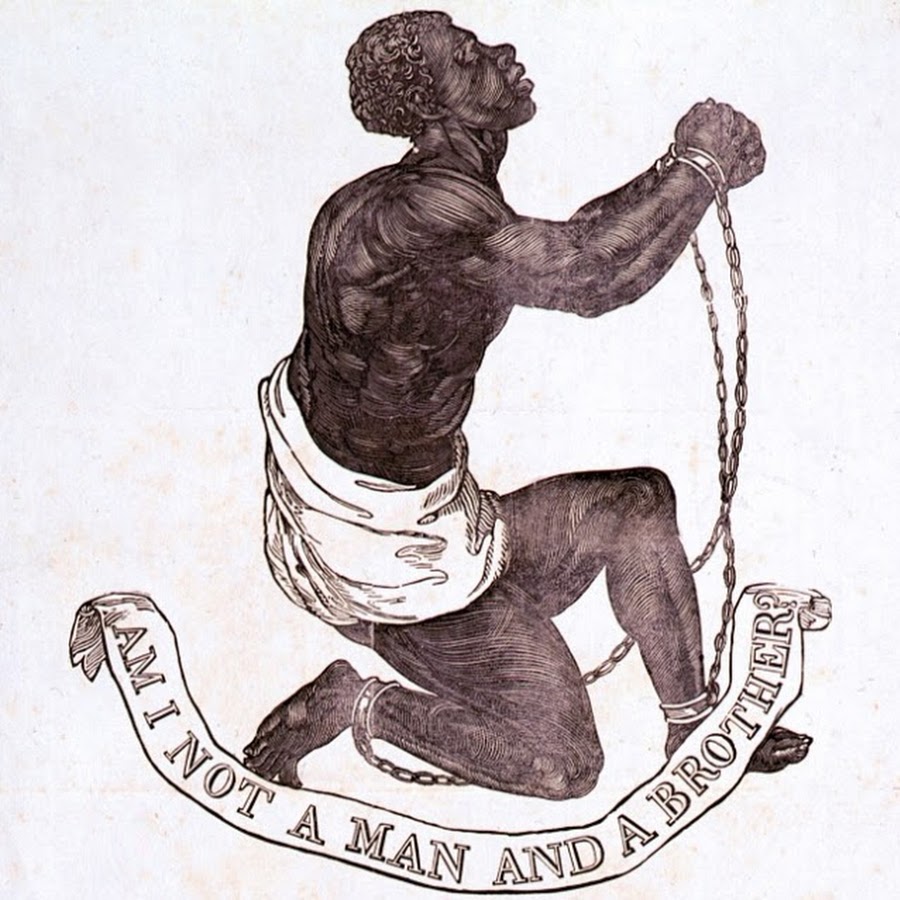

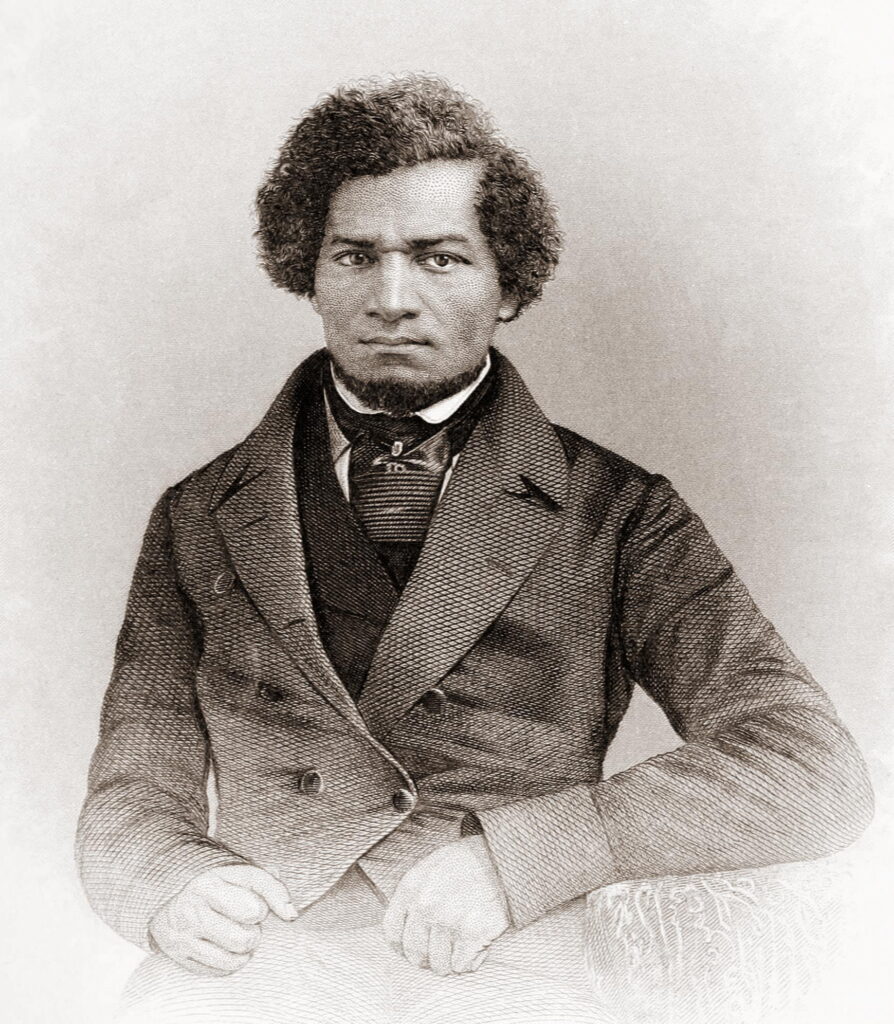

Throughout My Bondage, My Freedom, Frederick Douglass presents numerous philosophical and moral arguments against slavery. Douglass describes all the white people involved in slavery, not just owners, as so corrupted by the the physical, emotional and sexual depravity of slavery that it’s hard to imagine he thought moral arguments would change the minds of these pro-slavery advocates.

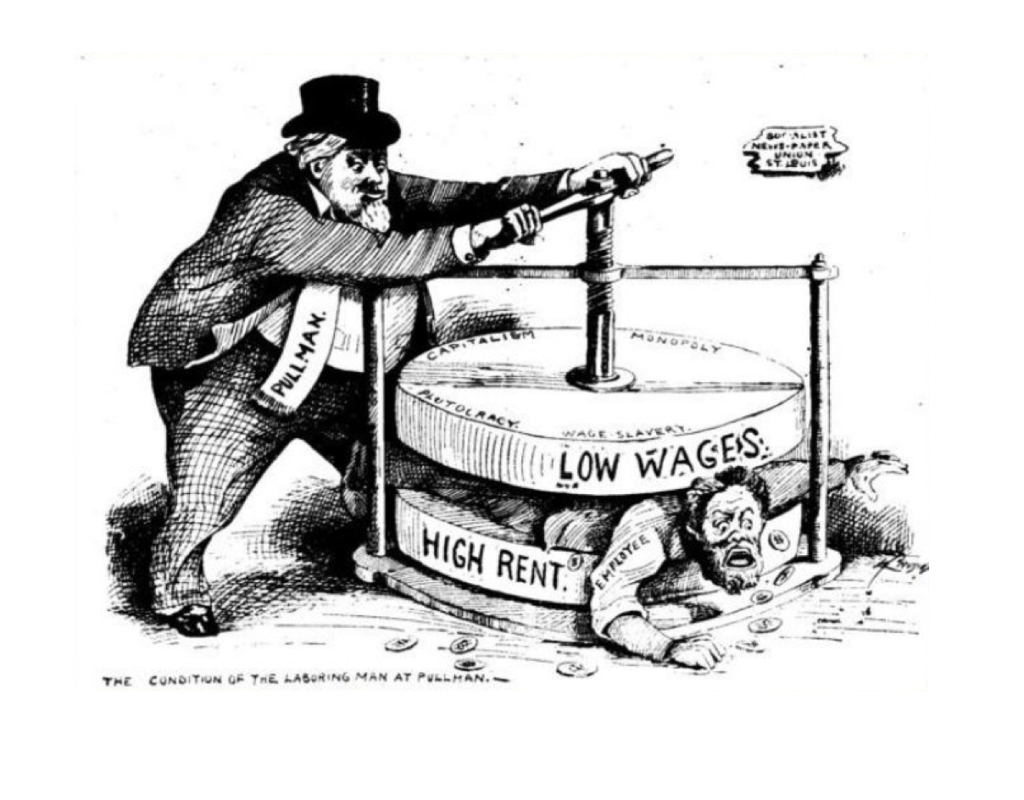

Douglass reasons that all oppression is motivated by pride, power, and crucially, avarice (Ch. 11). Greed motivates slave owners, whom he calls “robbers” (Ch. 11, 20, 21). Most people are not slave owners, though, even in the South. Plantation owners were, in a sense, the wealthy elite of their day, owning the equivalent of multinational corporations working within global trade networks. Enslaved people were obviously aware of the theft perpetrated by owners and so be unsupportive of slavery, but why would working-class people in the South, people who didn’t own slaves, without slaves, support the institution of slavery? It’s obvious what the plantation owners are getting, but what is the working-class getting?

In chapter twenty, Douglass addresses this question and makes a sophisticated critique of the economics of slavery. Slave owners made profit off of the essentially free labor they used to cultivate their labor-intensive crops like cotton, tobacco and sugar. Douglass seeks to show that while cheap, slave labor is tremendously inefficient It also makes it so that free laborers must compete on the labor-market with people who essentially take no wages. If working-class people were able to bring about emancipation, Douglass reasons, it would bring a bout a more economically fair world for everyone, including white (and non-Black) workers. Douglass sees explaining this as an “important element in the overthrow of the slave system” (Ch. 20).

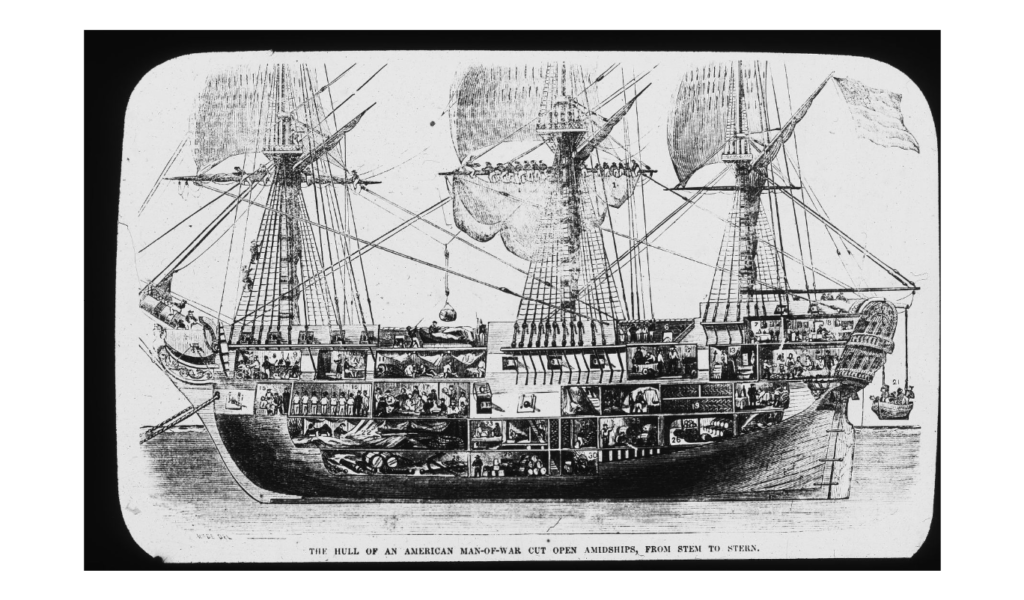

In chapter twenty, Douglass returns to Baltimore after his time with Covey where he performed field labor, generally considered the most basic of labor. Douglass compares himself to an ox used for plowing while with Covey, suggesting that his only use was as brute strength (Ch. 15). In Baltimore, though, Douglass goes to work in a shipyard as a caulker. Unlike field labor, caulking is a skilled trade, meaning you need to be trained to do it and it takes practice to do it efficiently. While Douglass has some previous experience caulking, he is not yet efficient.

Douglass’ overseer in the Baltimore boatyard is Mr. Gardiner and he has several large military contracts and is under a deadline whereby he must pay a significant penalty if he fails to have the ships ready to launch by July—probably to be commissioned on Independence Day. Douglass describes the scene as “all was hurry and driving.”

The most logical strategy for Mr. G, as Douglass later calls him, is to have Douglass work alongside an experienced caulker. That way Douglass would become more skilled and his labor would be more valuable because he would do more high-quality work in a shorter amount of time. Instead, Douglass is appointed everyone’s assistant. “This was placing me at the beck and call of about seventy-five men,” he complains, “I was to regard all these as masters. Their word was to be my law.”

Unable to help everyone, his “masters” increasingly become frustrated and their comments increasingly become racial attacks, referring to him as “nigger” and “darkey” and threatening violence. This racial violence continues for eight months until Douglass is savagely beaten, nearly to death, by the (white) carpenters. The image he sketches is graphic, describing his body as “mangled,” one eye “nearly knocked out of its socket.”

How do we explain the white carpenters ganging up on Douglass? It would be easy to claim racism, but Douglass instead argues that the white laborers are following a rational logic: as a slave, Douglass’ forced free labor undercuts the ability of white laborers to get fair wages for their own work. Douglass declares the problem is “the conflict of slavery with the interests of the white mechanics and laborers of the south” (emphasis original). In other words, while slavery is lucrative for the slave owner, cheap black labor is in direct competition with white labor and instead of blaming slaves, white laborers should join with enslaved people against the rich plantation owners.

As he elaborates his theory, Douglass argues unequivocally that the wage-labor common in cities is slavery by another name. While Black slaves are directly deprived of the resources necessary to sustain life by slave owners (food, shelter, clothing, love); Laborers are deprived the resources necessary to sustain life by artificially low wages (that prevent them from affording food, shelter, clothing, love).

Douglass charges that plantation owners use white supremacy against both Black people and poor White people. In both cases, it works to deprive the people of the true value of their work for profit of the owner. In the case of free laborer, racism acts as a distraction from the reality so that he is proud of being white rather than seeing himself as in the same boat as the slave. Therefore, one of the routes to getting emancipation is to show the non-Black working class how it stands to benefit.

It’s another way of saying “We are the 99%.”

The rest of the passage is below:

In the country, this conflict is not so apparent; but, in cities, such as Baltimore, Richmond, New Orleans, Mobile, &c., it is seen pretty clearly. The slaveholders, with a craftiness peculiar to themselves, by encouraging the enmity of the poor, laboring white man against the blacks, succeeds in making the said white man almost as much a slave as the black slave himself. The difference between the white slave, and the black slave, is this: the latter belongs to one slaveholder, and the former belongs to all the slaveholders, collectively. The white slave has taken from him, by indirection, what the black slave has taken from him, directly, and without ceremony. Both are plundered, and by the same plunderers. The slave is robbed, by his master, of all his earnings, above what is required for his bare physical necessities; and the white man is robbed by the slave system, of the just results of his labor, because he is flung into competition with a class of laborers who work without wages. The competition, and its injurious consequences, will, one day, array the non-slaveholding white people of the slave states, against the slave system, and make them the most effective workers against the great evil. At present, the slaveholders blind them to this competition, by keeping alive their prejudice against the slaves, as men—not against them as slaves. They appeal to their pride, often denouncing emancipation, as tending to place the white working man, on an equality with negroes, and, by this means, they succeed in drawing off the minds of the poor whites from the real fact, that, by the rich slave-master, they are already regarded as but a single remove from equality with the slave. The impression is cunningly made, that slavery is the only power that can prevent the laboring white man from falling to the level of the slave’s poverty and degradation. To make this enmity deep and broad, between the slave and the poor white man, the latter is allowed to abuse and whip the former, without hinderance. But—as I have suggested—this state of facts prevails mostly in the country. In the city of Baltimore, there are not unfrequent murmurs, that educating the slaves to be mechanics may, in the end, give slave-masters power to dispense with the services of the poor white man altogether. But, with characteristic dread of offending the slaveholders, these poor, white mechanics in Mr. Gardiner’s ship-yard—instead of applying the natural, honest remedy for the apprehended evil, and objecting at once to work there by the side of slaves—made a cowardly attack upon the free colored mechanics, saying they were eating the bread which should be eaten by American freemen, and swearing that they would not work with them. The feeling was, really, against having their labor brought into competition with that of the colored people at all; but it was too much to strike directly at the interest of the slaveholders; and, therefore—proving their servility and cowardice—they dealt their blows on the poor, colored freeman, and aimed to prevent him from serving himself, in the evening of life, with the trade with which he had served his master, during the more vigorous portion of his days. Had they succeeded in driving the black freemen out of the ship yard, they would have determined also upon the removal of the black slaves. The feeling was very bitter toward all colored people in Baltimore, about this time, (1836,) and they—free and slave—suffered all manner of insult and wrong.

Douglass, Frederick. “Chapter Twenty.” My Bondage, My Freedom. 1855.