Check the schedule for the list of what is due today. Mostly, it’s going over the syllabus, getting on the tools, etc. The real reading and work is due tomorrow (but there’s no reason you can’t get started on the reading, if you wanted to.)

Frederick Douglass’ Economic Critique of Racism in My Bondage, My Freedom

Throughout My Bondage, My Freedom, Frederick Douglass presents numerous philosophical and moral arguments against slavery. Douglass describes all the white people involved in slavery, not just owners, as so corrupted by the the physical, emotional and sexual depravity of slavery that it’s hard to imagine he thought moral arguments would change the minds of these pro-slavery advocates.

Douglass reasons that all oppression is motivated by pride, power, and crucially, avarice (Ch. 11). Greed motivates slave owners, whom he calls “robbers” (Ch. 11, 20, 21). Most people are not slave owners, though, even in the South. Plantation owners were, in a sense, the wealthy elite of their day, owning the equivalent of multinational corporations working within global trade networks. Enslaved people were obviously aware of the theft perpetrated by owners and so be unsupportive of slavery, but why would working-class people in the South, people who didn’t own slaves, without slaves, support the institution of slavery? It’s obvious what the plantation owners are getting, but what is the working-class getting?

In chapter twenty, Douglass addresses this question and makes a sophisticated critique of the economics of slavery. Slave owners made profit off of the essentially free labor they used to cultivate their labor-intensive crops like cotton, tobacco and sugar. Douglass seeks to show that while cheap, slave labor is tremendously inefficient It also makes it so that free laborers must compete on the labor-market with people who essentially take no wages. If working-class people were able to bring about emancipation, Douglass reasons, it would bring a bout a more economically fair world for everyone, including white (and non-Black) workers. Douglass sees explaining this as an “important element in the overthrow of the slave system” (Ch. 20).

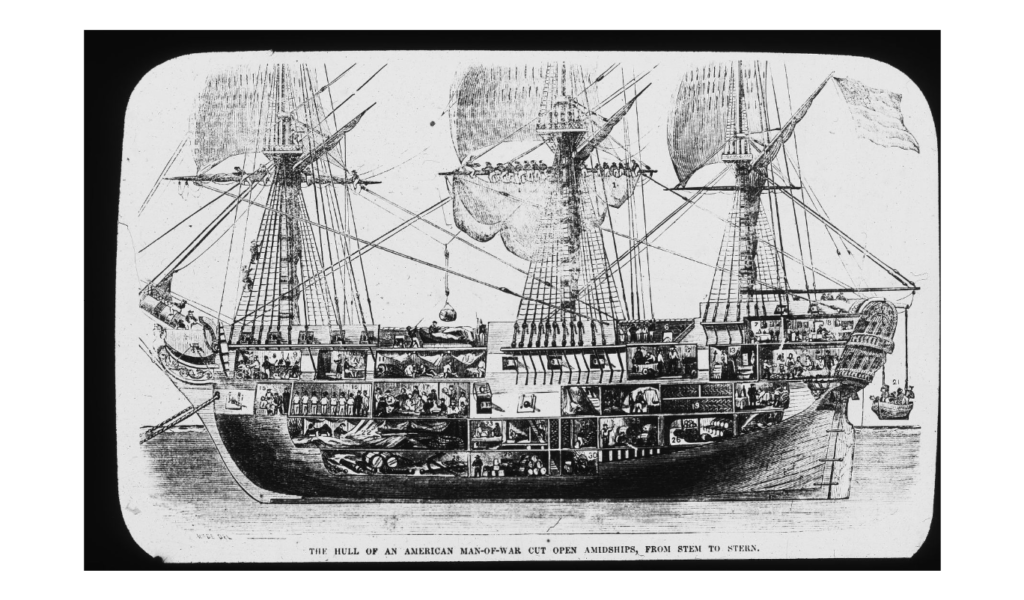

In chapter twenty, Douglass returns to Baltimore after his time with Covey where he performed field labor, generally considered the most basic of labor. Douglass compares himself to an ox used for plowing while with Covey, suggesting that his only use was as brute strength (Ch. 15). In Baltimore, though, Douglass goes to work in a shipyard as a caulker. Unlike field labor, caulking is a skilled trade, meaning you need to be trained to do it and it takes practice to do it efficiently. While Douglass has some previous experience caulking, he is not yet efficient.

Douglass’ overseer in the Baltimore boatyard is Mr. Gardiner and he has several large military contracts and is under a deadline whereby he must pay a significant penalty if he fails to have the ships ready to launch by July—probably to be commissioned on Independence Day. Douglass describes the scene as “all was hurry and driving.”

The most logical strategy for Mr. G, as Douglass later calls him, is to have Douglass work alongside an experienced caulker. That way Douglass would become more skilled and his labor would be more valuable because he would do more high-quality work in a shorter amount of time. Instead, Douglass is appointed everyone’s assistant. “This was placing me at the beck and call of about seventy-five men,” he complains, “I was to regard all these as masters. Their word was to be my law.”

Unable to help everyone, his “masters” increasingly become frustrated and their comments increasingly become racial attacks, referring to him as “nigger” and “darkey” and threatening violence. This racial violence continues for eight months until Douglass is savagely beaten, nearly to death, by the (white) carpenters. The image he sketches is graphic, describing his body as “mangled,” one eye “nearly knocked out of its socket.”

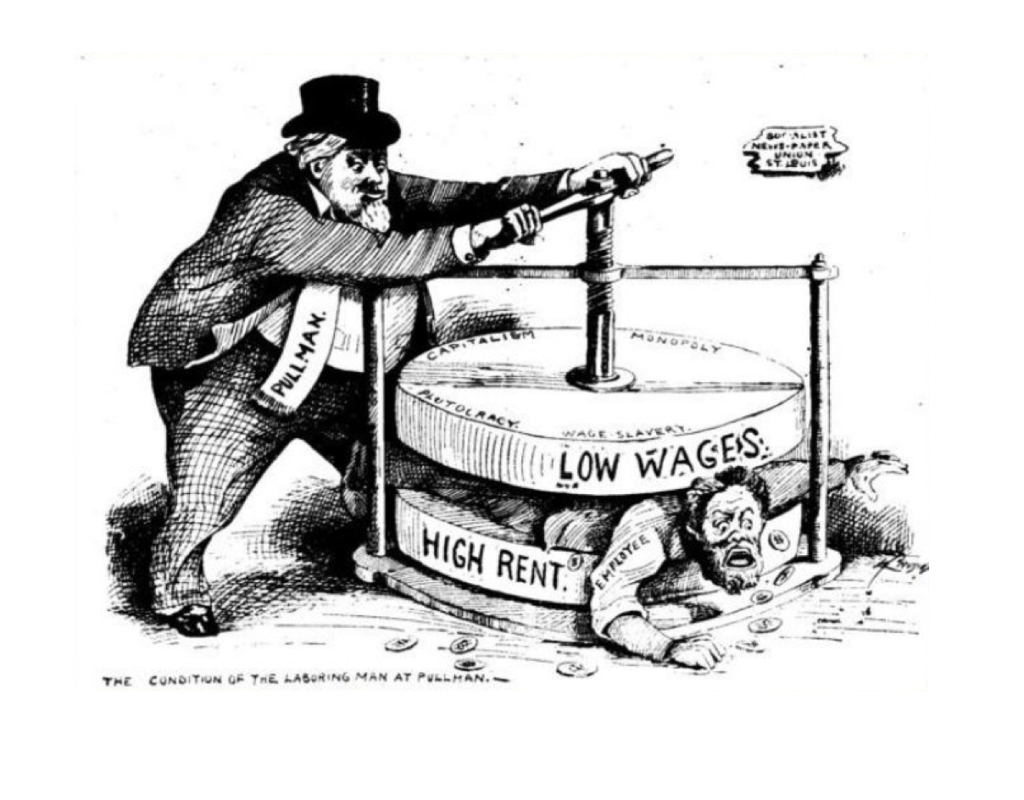

How do we explain the white carpenters ganging up on Douglass? It would be easy to claim racism, but Douglass instead argues that the white laborers are following a rational logic: as a slave, Douglass’ forced free labor undercuts the ability of white laborers to get fair wages for their own work. Douglass declares the problem is “the conflict of slavery with the interests of the white mechanics and laborers of the south” (emphasis original). In other words, while slavery is lucrative for the slave owner, cheap black labor is in direct competition with white labor and instead of blaming slaves, white laborers should join with enslaved people against the rich plantation owners.

As he elaborates his theory, Douglass argues unequivocally that the wage-labor common in cities is slavery by another name. While Black slaves are directly deprived of the resources necessary to sustain life by slave owners (food, shelter, clothing, love); Laborers are deprived the resources necessary to sustain life by artificially low wages (that prevent them from affording food, shelter, clothing, love).

Douglass charges that plantation owners use white supremacy against both Black people and poor White people. In both cases, it works to deprive the people of the true value of their work for profit of the owner. In the case of free laborer, racism acts as a distraction from the reality so that he is proud of being white rather than seeing himself as in the same boat as the slave. Therefore, one of the routes to getting emancipation is to show the non-Black working class how it stands to benefit.

It’s another way of saying “We are the 99%.”

The rest of the passage is below:

In the country, this conflict is not so apparent; but, in cities, such as Baltimore, Richmond, New Orleans, Mobile, &c., it is seen pretty clearly. The slaveholders, with a craftiness peculiar to themselves, by encouraging the enmity of the poor, laboring white man against the blacks, succeeds in making the said white man almost as much a slave as the black slave himself. The difference between the white slave, and the black slave, is this: the latter belongs to one slaveholder, and the former belongs to all the slaveholders, collectively. The white slave has taken from him, by indirection, what the black slave has taken from him, directly, and without ceremony. Both are plundered, and by the same plunderers. The slave is robbed, by his master, of all his earnings, above what is required for his bare physical necessities; and the white man is robbed by the slave system, of the just results of his labor, because he is flung into competition with a class of laborers who work without wages. The competition, and its injurious consequences, will, one day, array the non-slaveholding white people of the slave states, against the slave system, and make them the most effective workers against the great evil. At present, the slaveholders blind them to this competition, by keeping alive their prejudice against the slaves, as men—not against them as slaves. They appeal to their pride, often denouncing emancipation, as tending to place the white working man, on an equality with negroes, and, by this means, they succeed in drawing off the minds of the poor whites from the real fact, that, by the rich slave-master, they are already regarded as but a single remove from equality with the slave. The impression is cunningly made, that slavery is the only power that can prevent the laboring white man from falling to the level of the slave’s poverty and degradation. To make this enmity deep and broad, between the slave and the poor white man, the latter is allowed to abuse and whip the former, without hinderance. But—as I have suggested—this state of facts prevails mostly in the country. In the city of Baltimore, there are not unfrequent murmurs, that educating the slaves to be mechanics may, in the end, give slave-masters power to dispense with the services of the poor white man altogether. But, with characteristic dread of offending the slaveholders, these poor, white mechanics in Mr. Gardiner’s ship-yard—instead of applying the natural, honest remedy for the apprehended evil, and objecting at once to work there by the side of slaves—made a cowardly attack upon the free colored mechanics, saying they were eating the bread which should be eaten by American freemen, and swearing that they would not work with them. The feeling was, really, against having their labor brought into competition with that of the colored people at all; but it was too much to strike directly at the interest of the slaveholders; and, therefore—proving their servility and cowardice—they dealt their blows on the poor, colored freeman, and aimed to prevent him from serving himself, in the evening of life, with the trade with which he had served his master, during the more vigorous portion of his days. Had they succeeded in driving the black freemen out of the ship yard, they would have determined also upon the removal of the black slaves. The feeling was very bitter toward all colored people in Baltimore, about this time, (1836,) and they—free and slave—suffered all manner of insult and wrong.

Douglass, Frederick. “Chapter Twenty.” My Bondage, My Freedom. 1855.

Frederick Douglass’ “Second Sight” and his Philosophical Critique of Slavery, Theory of Man

“[The Negro] is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

DuBois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. 1903

“From the 16th century onwards, a seventh son (or, more rarely, seventh daughter) was widely thought to have psychic powers, usually as a healer, but sometimes as a dowser or fortune-teller; even more powerful was one whose father (or mother) was also a seventh son (or daughter).”

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud. A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford, 2003.

“One of the most persistent folk beliefs about childbirth concerns the good luck attendant on a child ‘born with the veil.’ The veil, or caul, is a membrane of the amniotic sac which contains the fluid and fetus. On occasion a child is born partially or entirely covered with this cloth-like membrane. . . The conviction that a child born thus will have the power to see and hear ghosts and to fortell the future is a widespread belief in Europe. . . Dickens’ David Copperfield [was born veiled.]”

Rich, Carroll Y. Born with the Veil: Black Folklore in Louisiana. The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 89, no. 353 (Jul. – Sep., 1976), pp. 328-331.

Part I: DuBois’ Concept of Double Consciousness and American Experience

In 1903, W. E. B. DuBois published The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of essays addressing the history and sociology of Black Americans. DuBois was the first African American to receive a PhD from Harvard University and is considered by many to be a an intellectual successor to Frederick Douglass. The first quotation above is from the first chapter of Souls in which DuBois lays out his theory of double-consciousness.

All Black people, DuBois argues, are born special—like the small percentage of children born en caul. Black people born in America, he continues, have a special role: they are prophets who can see beyond their current world. He is using the superstitious connotations of a biological condition as a metaphor for the unique perspective of Black people in America, people who are also affected by the superstitious connotations of the melanin in their skin, called racism. But what does DuBois mean by this second-sight? To answer that question it helps to first understand what DuBois argues is the cause of this ability.

As a man of science, DuBois doesn’t believe in superstitions like fortune-telling. Instead, as a sociologist, DuBois predictably sees the cause for this unique ability of Black Americans to be the culture of America. He describes this second-sight as a feeling of always seeing yourself through the eyes of someone else.

Consider for a moment, Frederick Douglass discusses in the first chapter of his autobiography that as a slave he has no idea of what his birthday is. This detail differentiates Douglass from the other (white) boys his age in ways even he, as a young child, understands. Douglass is not a white person: they have birthdays. The fact that Douglass’ day of birth is unimportant is meant to reinforce for Douglass that his birth is unimportant; he is, after all in the logical of slavery, just property. I don’t know the birthday or age of my cat, for instance. Unlike my cat, though, Douglass knows he’s important. He has a loving home with his grandmother.

This is the second-sight that DuBois is writing about. Even as a child, Douglass is aware that the slave owners (and perhaps “white” people in general) are trying to put Douglass in a specific box, that of a slave, a brute, an animal. Douglass is keenly aware of this at all times. It’s reflected in his lack of birthday, his clothing, his meals, the way he’s expected to behave, the family that is around him, the way he is allowed to express himself, what he’s allowed to learn, the work he’s allowed to do and when he’s allowed to do it. . . I could go on and on.

In most of these situations, Douglass understand his status as a slave as one of negation. He doesn’t have things because he is not a (white) owner. This is likely what DuBois means when he writes that America is, for the the Black person “a world which yields him no true self-consciousness.” Racism in American prevents Black folks from living a kind of true, authentic self because of repression, but Black folks also know the lie inherent lies of the racist’s view.

Perhaps think of it as DuBois arguing that Black folks haven’t had room to really see what they can do, but they know damn well it’s not going to look like how things are now.

This is a powerful position for critique. You are on the outside of a system in a sense, you can critique how it is unjust. But since you don’t yet know you’re own capacity, it’s a space where you can also imagine new capacities and configurations. If we know the world does not look like this the next logical question is what should it look like?

I would argue that Douglass sees himself as an American philosopher, pulling aside the veil and seeking the truth of the way things are and he’s very skeptical of how folks who have not experienced the torture of white supremacy will be able to have as clear vision as him.

Part II: Douglass and the Abolitionists

Read through chapter twenty-three. Douglass recounts his experience working with the Abolitionists, most notably William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the most well-known Abolitionist society in the country.

The American Anti-Slavery Society was well-respected and Douglass gets his start as a national figure with it, but he has a public break with Garrison a few years before this autobiography is published. The Anti-Slavery Society membership was composed overwhelmingly of white Northerners and Douglass wanted to work primarily in Black communities. It might be helpful to think of this chapter as a critique of what is now called white allyship.

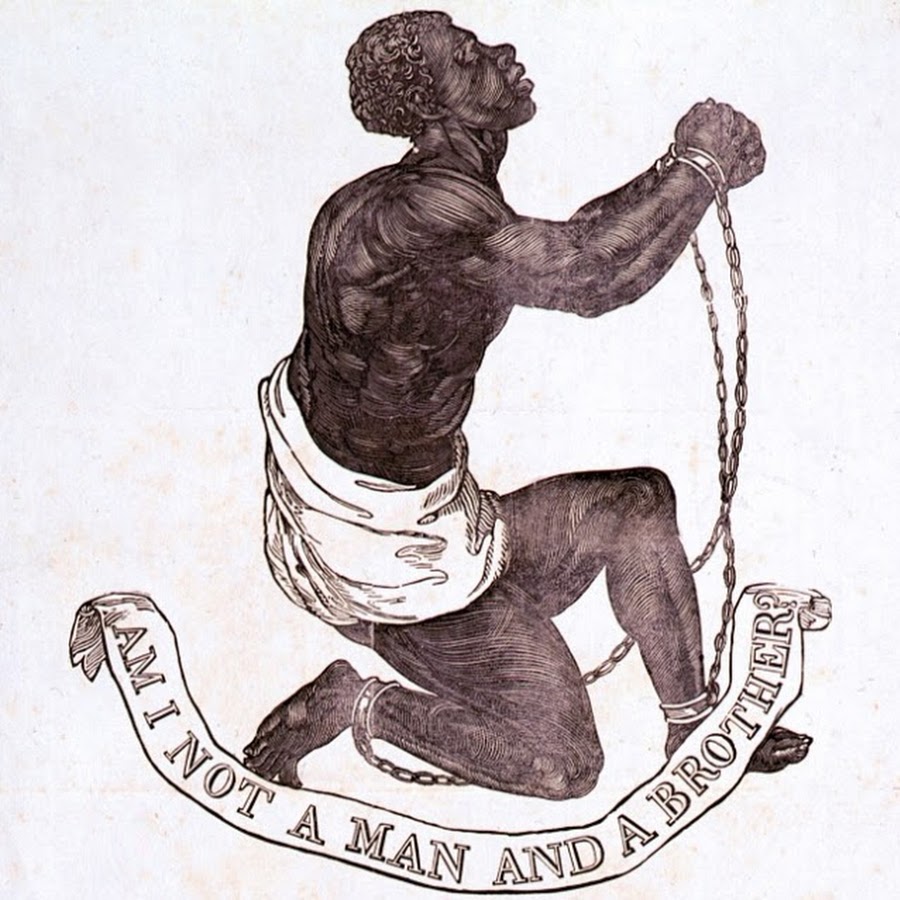

One point that might have irked Douglass is the way enslaved people were depicted by abolitionists. The image below is very common in Abolitionist circles: it was made into commemorative coins, pins, flags, placed on postcards, ceramics, anything. It evokes the dominant Abolitionist narrative that enslaved people needed white folks to bring about emancipation because white folks who had the political power of the vote. In fact, it wasn’t even white folks generally, but specifically white men (because only they had the vote).

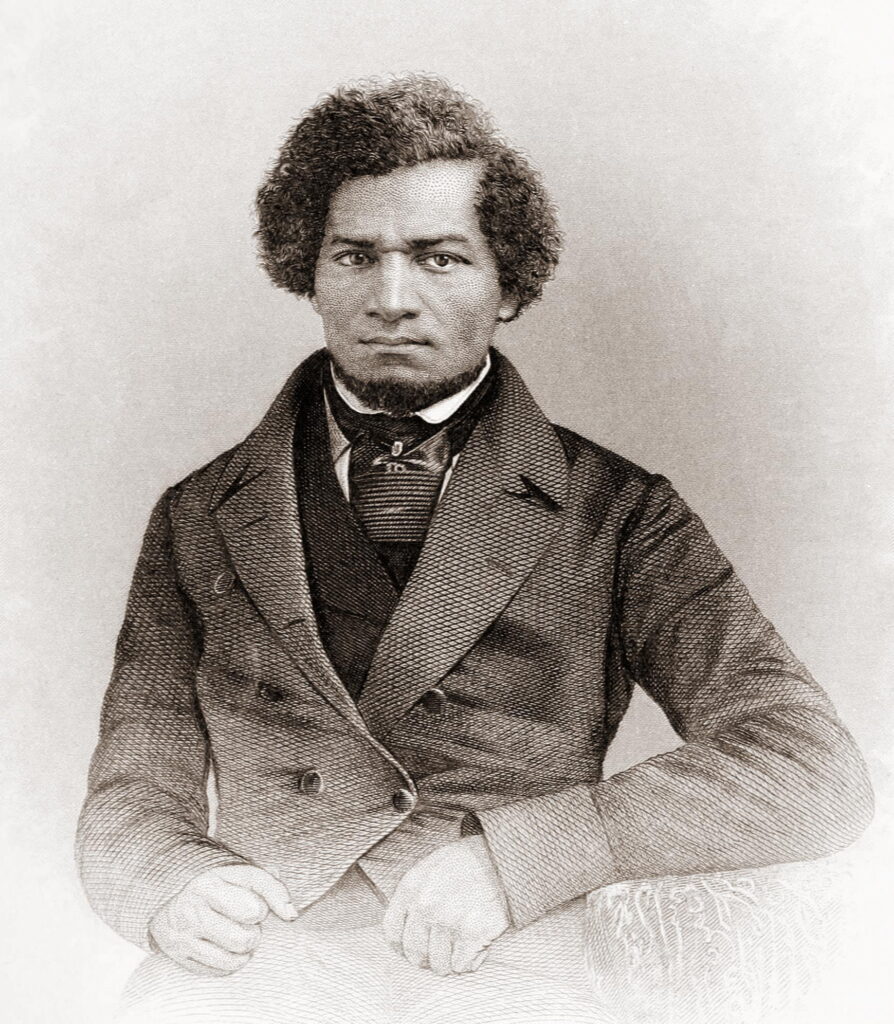

It seems obvious that to someone who, like Douglass, defined himself by self-reliance and self-defense, this is image is absurd. It doesn’t look how Douglass presented himself in photographs.

Because of the public break between Douglass and the anti-slavery society, readers at the time likely expected a discussion of why. But it would also make sense that would tread carefully; he’s likely not eager to make enemies with people working toward a common cause, even if he disagrees with them as evidenced by his separation. With careful reading, you’ll see that Douglass often uses humility to hide his most savage criticism.

For instance, Douglass reports that he doesn’t remember the speech he makes in Nantucket at all, describing himself as having difficulty “stand[ing] erect,” or to “command and articulate two words without hesitation and stammering.” How does that compare to the Douglass we’ve seen earlier in the work who remembers whole speeches he supposedly said to himself in the woods when he’s 16? How does this compare to the adult Douglass we’ve come to know?

The audience doesn’t seem to know how to react. It’s as quiet as before but there’s a new energy. Douglass had previously written about taking satisfaction in making his white playmates feel uncomfortable with critiques of slavery, perhaps this is the effect he had on his audience. Douglass is either ambivalent about his effect on the audience or he downplays it by saying he forgets it and doesn’t even know if whether he “had made an eloquent speech in behalf of freedom or not.”

C’mon. . . do you think Douglass made a bad speech about freedom?

What people remember, he writes, is Garrison’s speech. Oddly, Douglass reports that Garrison is largely preaching to the choir, so to speak, writing “Those who had heard Mr. Garrison oftenest, and had known him longest, were astonished. It was an effort of unequaled power, sweeping down, like a very tornado, every opposing barrier, whether of sentiment or opinion.”

But whereas Douglass had spoken about Freedom, Garrison had taken Douglass, as his text, meaning while Douglass was talking about Freedom as a concept from his experience (i.e. in philosophical/rational terms), Garrison freely interprets Douglass’ life, turning it into a text to be used as a metaphor.

In the first chapter of My Bondage, Douglass describes his awareness that his is born for someone else. The role of a slave is to have all of your faculties controlled by someone else, even your life story and decisions. It’s easy to imagine Douglass unhappiness at suddenly losing control of his own life and watching it used for different purposes. It may even bring a new meaning to the term “slave narrative,” in which Douglass own story is enslaved to serve Garrison’s purpose.

Read through the chapter with this same eye for Douglass receding into the background and using his “second-sight” to see how Garrison and other white abolitionists see him. Try to draw comparisons for how Garrison describes Douglass and how he would describe himself. Try to account for what might result in those kinds of differences. As usual, questions are always welcome.

Annotating Manifold Texts

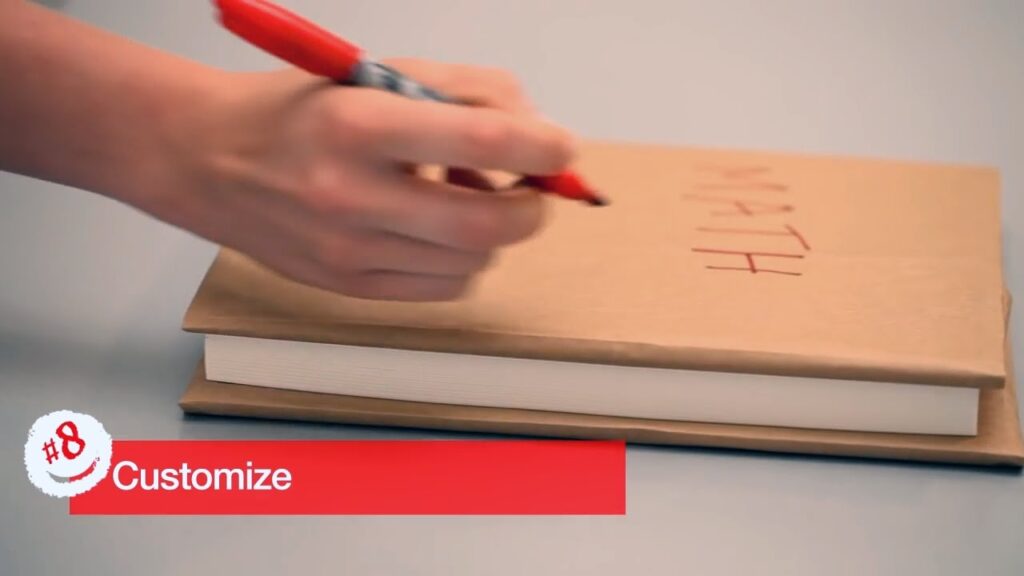

When I was younger I used to keep my books perfectly clean. I’d certainly never write in them.

Maybe it was because many of my books were loaned from school. Library books, sure, but also the ones where you’d be told to put a paper cover on it and write your name in the front so you could be found if your textbook was revealed to teachers as defaced. Even when I was in college and had to buy my own books I didn’t like to write in them — even when others had because I’d bought used copies.

That’s not true anymore. I annotate the heck out of my books. Seriously. Sometimes I have more notes than there is text on the page! Sometimes they’re dumb comments (you’d be surprised how often I write “this is dumb” in a margin or “WTF???”. Sometimes though I make interesting connections or predictions.

Usually, I forget about these in-the-moment notes until I have to go back and write about a work. Then I find it filled with my notes, thoughts, and ideas that I’d forgotten about. The passages I thought were the most important? Marked! And with my thoughts. It’s incredibly helpful (and occasionally funny) to see annotations I’ve made.

That’s why I’d like you to get in the habit of annotating your texts. You don’t have to continue the practice outside of this class, but for now try it. We’re using Manifold for (most) of our texts, an app that makes highlighting and writing notes very easy to do. On each assignment for a new text you’ll be asked to “READ AND ANNOTATE,” which means read and make notes as you go along. You’ll see the notes from your fellow classmates (and sometimes other classes) as well. These notes are helpful to the person who made them but there’s no reason you should ignore them. Your notes might help someone else, too.

So what should you annotate? The easy answer is anything. Seriously. Whatever strikes your fancy. If there’s a line that just rolls off the tongue and sounds good in your ears, you might highlight it. Or you might make a note: “!!!” or “Great line!” If a line confuses you, you might write in a note what you think is happening and hope another reader will help clarify the situation for you, after reading your question. You might fill in definitions of words (you may not know, for instance, that ague is the 19th-century word for malaria, or that consumption is tuberculosis, or (not move away from diseases) that a phaeton is a type of two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. You might also write in theories or brief notes about symbols or predictions of what will happen.

Follow this link for specific instructions on how to annotate a Manifold text: https://manifoldapp.org/docs/reading/annotating

The benefit of annotation is that you don’t have to remember everything you’re thinking as your reading. That’s a big deal. How many phone numbers do you remember? Probably not many because you trust you phone to remember them. This is the same principle. Let your book, in this case a digital one, be your memory. The best part about collaborating on annotation, as we’ll be doing in this class is that everyone’s notes can be a benefit.

If your shy, don’t sweat it. Hopefully your username is something anonymous, so no one will know who you are. I won’t be grading you on your annotations, although if I see some that really blow my socks off, it’s hard to imagine I won’t reach out to that person an say “right on!”

There’s no right or wrong way to annotate. These are notes primarily for you. If you like complete sentences, go for it. If you dash off key words, go for it. If links to Wiki articles or other online resources are helpful, post them. You’ll always have access to these works and notes, so you can do whatever you want.

I’ll end with this poem about annotation:

Marginalia

By Billy Collins

Collins. Billy. “Marginalia.” Poetry, (Jan. 1996), pp. 249-251.

Sometimes the notes are ferocious,

skirmishes against the author

raging along the borders of every page

in tiny black script.

If I could just get my hands on you,

Kierkegaard, or Conor Cruise O’Brien,

they seem to say,

I would bolt the door and beat some logic into your head.

Other comments are more offhand, dismissive –

‘Nonsense.’ ‘Please! ‘ ‘HA! ! ‘ –

that kind of thing.

I remember once looking up from my reading,

my thumb as a bookmark,

trying to imagine what the person must look like

why wrote ‘Don’t be a ninny’

alongside a paragraph in The Life of Emily Dickinson.

Students are more modest

needing to leave only their splayed footprints

along the shore of the page.

One scrawls ‘Metaphor’ next to a stanza of Eliot’s.

Another notes the presence of ‘Irony’

fifty times outside the paragraphs of A Modest Proposal.

Or they are fans who cheer from the empty bleachers,

Hands cupped around their mouths.

‘Absolutely,’ they shout

to Duns Scotus and James Baldwin.

‘Yes.’ ‘Bull’s-eye.’ ‘My man! ‘

Check marks, asterisks, and exclamation points

rain down along the sidelines.

And if you have managed to graduate from college

without ever having written ‘Man vs. Nature’

in a margin, perhaps now

is the time to take one step forward.

We have all seized the white perimeter as our own

and reached for a pen if only to show

we did not just laze in an armchair turning pages;

we pressed a thought into the wayside,

planted an impression along the verge.

Even Irish monks in their cold scriptoria

jotted along the borders of the Gospels

brief asides about the pains of copying,

a bird signing near their window,

or the sunlight that illuminated their page-

anonymous men catching a ride into the future

on a vessel more lasting than themselves.

And you have not read Joshua Reynolds,

they say, until you have read him

enwreathed with Blake’s furious scribbling.

Yet the one I think of most often,

the one that dangles from me like a locket,

was written in the copy of Catcher in the Rye

I borrowed from the local library

one slow, hot summer.

I was just beginning high school then,

reading books on a davenport in my parents’ living room,

and I cannot tell you

how vastly my loneliness was deepened,

how poignant and amplified the world before me seemed,

when I found on one page

A few greasy looking smears

and next to them, written in soft pencil-

by a beautiful girl, I could tell,

whom I would never meet-

‘Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.’

Elements of the Academic Essay

By David Harvey, Harvard University

1. Thesis: your main insight or idea about a text or topic, and the main proposition that your essay demonstrates. It should be true but arguable (not obviously or patently true, but one alternative among several), be limited enough in scope to be argued in a short composition and with available evidence, and get to the heart of the text or topic being analyzed (not be peripheral). It should be stated early in some form and at some point recast sharply (not just be implied), and it should govern the whole essay (not disappear in places).

2. Motive: the intellectual context that you establish for your topic and thesis at the start of your essay, in order to suggest why someone, besides your instructor, might want to read an essay on this topic or need to hear your particular thesis argued—why your thesis isn’t just obvious to all, why other people might hold other theses (that you think are wrong). Your motive should be aimed at your audience: it won’t necessarily be the reason you first got interested in the topic (which could be private and idiosyncratic) or the personal motivation behind your engagement with the topic. Indeed it’s where you suggest that your argument isn’t idiosyncratic, but rather is generally interesting. The motive you set up should be genuine: a misapprehension or puzzle that an intelligent reader (not a straw dummy) would really have, a point that such a reader would really overlook. Defining motive should be the main business of your introductory paragraphs, where it is usually introduced by a form of the complicating word “But.”

3. Evidence: the data—facts, examples, or details—that you refer to, quote, or summarize to support your thesis. There needs to be enough evidence to be persuasive; it needs to be the right kind of evidence to support the thesis (with no obvious pieces of evidence overlooked); it needs to be sufficiently concrete for the reader to trust it (e.g. in textual analysis, it often helps to find one or two key or representative passages to quote and focus on); and if summarized, it needs to be summarized accurately and fairly.

4. Analysis: the work of breaking down, interpreting, and commenting upon the data, of saying what can be inferred from the data such that it supports a thesis (is evidence for something). Analysis is what you do with data when you go beyond observing or summarizing it: you show how its parts contribute to a whole or how causes contribute to an effect; you draw out the significance or implication not apparent to a superficial view. Analysis is what makes the writer feel present, as a reasoning individual; so your essay should do more analyzing than summarizing or quoting.

5. Keyterms: the recurring terms or basic oppositions that an argument rests upon, usually literal but sometimes a ruling metaphor. These terms usually imply certain assumptions—unstated beliefs about life, history, literature, reasoning, etc. that the essayist doesn’t argue for but simply assumes to be true. An essay’s keyterms should be clear in their meaning and appear throughout (not be abandoned half-way); they should be appropriate for the subject at hand (not unfair or too simple—a false or constraining opposition); and they should not be inert clichés or abstractions (e.g. “the evils of society”). The attendant assumptions should bear logical inspection, and if arguable they should be explicitly acknowledged.

6. Structure: the sequence of main sections or sub-topics, and the turning points between them. The sections should follow a logical order, and the links in that order should be apparent to the reader (see “stitching”). But it should also be a progressive order—there should have a direction of development or complication, not be simply a list or a series of restatements of the thesis (“Macbeth is ambitious: he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitious here; and he’s ambitions here, too; thus, Macbeth is ambitious”). And the order should be supple enough to allow the writer to explore the topic, not just hammer home a thesis. (If the essay is complex or long, its structure may be briefly announced or hinted at after the thesis, in a road-map or plan sentence.)©Gordon Harvey, Harvard University2/2

7. Stitching: words that tie together the parts of an argument, most commonly (a) by using transition(linking or turning) words as signposts to indicate how a new section, paragraph, or sentence follows from the one immediately previous; but also (b) by recollection of an earlier idea or part of the essay, referring back to it either by explicit statement or by echoing key words or resonant phrases quoted or stated earlier. The repeating of key or thesis concepts is especially helpful at points of transition from one section to another, to show how the new section fits in.

8. Sources: persons or documents, referred to, summarized, or quoted, that help a writer demonstrate the truth of his or her argument. They are typically sources of (a) factual information or data, (b) opinions or interpretation on your topic, (c) comparable versions of the thing you are discussing, or (d) applicable general concepts. Your sources need to be efficiently integrated and fairly acknowledged by citation.

9. Reflecting: when you pause in your demonstration to reflect on it, to raise or answer a question about it—as when you (1) consider a counter-argument—a possible objection, alternative, or problem that a skeptical or resistant reader might raise; (2) define your terms or assumptions (what do I mean by this term? or, what am I assuming here?); (3) handle a newly emergent concern (but if this is so, then how can X be?); (4) draw out an implication (so what? what might be the wider significance of the argument I have made? what might it lead to if I’m right? or, what does my argument about a single aspect of this suggest about the whole thing? or about the way people live and think?), and (5) consider a possible explanation for the phenomenon that has been demonstrated (why might this be so? what might cause or have caused it?); (6) offer a qualification or limitation to the case you have made (what you’re not saying). The first of these reflections can come anywhere in an essay; the second usually comes early; the last four often come late (they’re common moves of conclusion).

10. Orienting: bits of information, explanation, and summary that orient the reader who isn’t expert in the subject, enabling such a reader to follow the argument. The orienting question is, what does my reader need here? The answer can take many forms: necessary information about the text, author, or event (e.g. given in your introduction); a summary of a text or passage about to be analyzed; pieces of information given along the way about passages, people, or events mentioned (including announcing or “set-up” phrases for quotations and sources). The trick is to orient briefly and gracefully.

11. Stance: the implied relationship of you, the writer, to your readers and subject: how and where you implicitly position yourself as an analyst. Stance is defined by such features as style and tone (e.g. familiar or formal); the presence or absence of specialized language and knowledge; the amount of time spent orienting a general, non-expert reader; the use of scholarly conventions of form and style. Your stance should be established within the first few paragraphs of your essay, and it should remain consistent.

12. Style: the choices you make of words and sentence structure. Your style should be exact and clear (should bring out main idea and action of each sentence, not bury it) and plain without being flat (should be graceful and a little interesting, not stuffy).

13. Title: It should both interest and inform. To inform—i.e. inform a general reader who might be browsing in an essay collection or bibliography—your title should give the subject and focus of the essay. To interest, your title might include a linguistic twist, paradox, sound pattern, or striking phrase taken from one of your sources (the aptness of which phrase the reader comes gradually to see). You can combine the interesting and informing functions in a single title or split them into title and subtitle. The interesting element shouldn’t be too cute; the informing element shouldn’t go so far as to state a thesis. Don’t underline your own title, except where it contains the title of another te